In my last article I discussed the role trust plays in creating high performing teams, in particular, the behaviours that build and break trust. Put simply, successful organisations are built on successful teams. Teams require trust in order to work effectively. Although we experience trust (and betrayal) at a deeply emotional level, trust is actually built and broken at a behavioural level by what we do. This article explores how to create the conditions for people in teams to change their behaviour in order to build greater trust.

Trust Begins with You

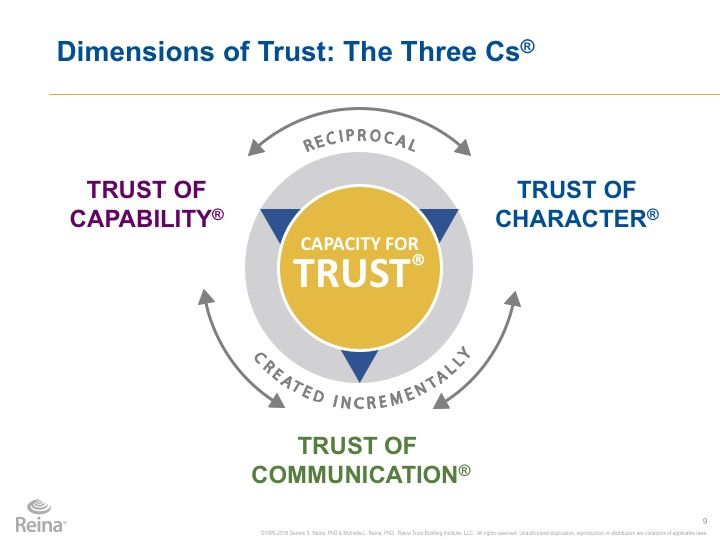

The work of Dennis and Michelle Reina identified 16 key behaviours, across three dimensions (see below), that build or break trust. If we engage in the behaviours that build trust, we dramatically improve the level of trust within a team. As trust increases, people feel safer, are more willing to take risks, and work together with clarity and purpose. However, if we continue to behave in ways that break trust, it is progressively eroded, resulting in disengaged team members and poorer performance.

This means that if a team wants to develop trust, people have to change the way they behave day to day. If they do not change their behaviour, the level of trust will not change, no matter how much everyone agrees that they “want to trust each other more”.

The Reinas’ research allows us to not only measure the level of perceived trust in a team, but also which behaviours specifically are helping build trust in the team, and which behaviours are obstructing it. Their instruments also allow the identification of both positive behaviours, and those negative behaviours that may be inadvertently contributing to a breakdown in trust in the team.

Once a team has a clear measure of their level of trust, and which behaviours are helping and which are hindering, they need to find a way to practice the positive behaviours more frequently, and to eradicate those that are undermining trust. This sounds simple enough but requires a fundamental shift in the way team members interact with each other, and a deep understanding of what influences such changes in behaviour.

As tempting as it is to focus on how we think others should change, the Reinas’ research has shown that successfully shifting trust starts with how each individual can change their own patterns of behaving. Herein lies the challenge. Anyone who has tried to change their own behaviour will know that sometimes, despite the best of intentions, we easily fall back into old habits. Think New Year’s resolutions, decisions to get fit, lose weight, eat healthy food. If trust in teams is behaviourally-based, how do we successfully change the way people in teams are behaving to achieve this?

The Inner Conformist Is Stronger Than The Inner Activist

There is no simple answer to this, but some significant advances in research in this area in recent years have identified a few critical factors that are important to understand if we are to successfully change behaviour.

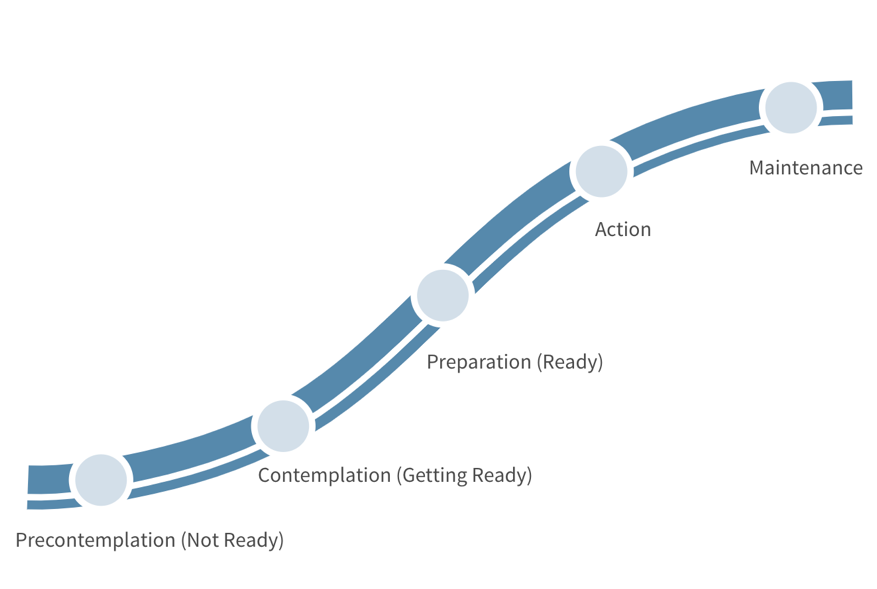

Firstly, changing behaviour is not a one-off event. Studies of over 150,000 participants found that changing behaviour is a process with identifiable stages (see diagram below), which most people need to move through in order to successfully change any sort of behaviour. This means that any intervention that is a one-off event, such as an off-site retreat or workshop is unlikely to have a long-lasting impact. This explains the common experience of teams participating in a one-day workshop, committing to actions, and then going back to the same behaviours the next day, week or month. Even with the best of intentions sooner or later people return to the old way of operating.

Secondly, this same research found that only a minority (usually less than 20%) of people are ready to take action at any given time. The implication of this is that interventions that are action-focused are likely to work at best with only 20% of the team. Even with consensus on what needs to change, the majority of people in the room are not going to be ready to change. Consequently, leaders and teams will need to find ways to support the 80% to move from the Precontemplation to Action phase, and to support the eventual transition from Action to the Maintenance phase. Depending on the behaviour that we are trying to change, this can take anywhere from six months to five years. Lasting change in behaviour is not going to happen overnight.

Thirdly, imploring people to “do the right thing” in one way or another is one of the least successful methods of triggering behavioural change in people. The reason for this is that we are more influenced by what others do than the inherent benefit of changing our behaviour.

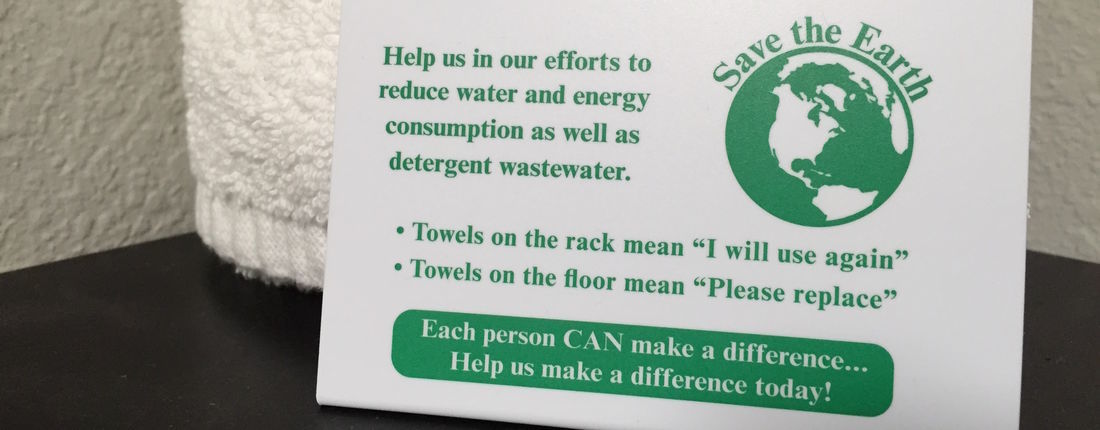

For example, we have all probably seen those signs in hotel bathrooms encouraging guests to reuse their towels. Robert Cialdini and his team conducted an experiment in 2008 where they randomly assigned three types of signs in the hotel rooms. The first contained the typical message inviting guests to show their respect for nature and help save the environment by re-using their towels during their stay. A second set of rooms had signs that informed guests “Almost 75% of guests who are asked to participate in our new resource savings program do help by using their towels more than once”. A third set of rooms had signs with an even more specific message describing how 75% of the guests who stayed in this particular room participated in their new resource savings program by using their towels more than once.

The results showed that nearly 25% more guests participated in the program when they thought the majority of other guests did the same thing, compared to the standard sign. This increased to more than 30% when the guests were informed that the majority of people who stayed in their room participated in the program. It turns out that individuals are driven to change their attitudes or behaviour in accordance with the standards of the group with whom they most closely identify – where there are similarities that are most meaningful. As Michael Morris, Professor of Psychology at Columbia University said, “The inner conformist is stronger than the inner activist”.

The implications of this for changing behaviour in teams is clear. Any sort of action that is focused on directing people to change the way they are behaving because it is the “right thing to do”, or appealing to their inner sense of virtue, is unlikely to succeed. For example, when organisations define their values and behaviours and encourage employees to “live these values”. Instead, to actually achieve a shift in the way team members behave, we may be more likely to succeed if we can tap into people’s desire to be part of the herd. By communicating how the majority of people were behaving, Cialdini was able to influence behaviour. Furthermore, the closer people can relate to the characteristics of the group the more likely they are to change. That is, the stronger the sense of “these people are like me” versus “not like me”, the more likely they are to change.

Finally, as human beings we have always explored new ideas, tested these out and adopted those that are beneficial. However, we are also creatures of habit, and for a new idea to be adopted it has to overcome the often well entrenched payoffs of the old attitude or behaviour.

When Peers Adopt A New Behaviour, It Is Hard Not To Follow Along

What has emerged recently from the research of Professor Sandy Pentland at MIT is that information alone is a weak motivator. To find out what does influence behaviour change, they used smart phones loaded with special software to track people’s social interactions in real time. The team collected more than five hundred thousand hours of data to examine what creates habits, and in particular, what they termed “Idea Flow”, or the propagation of behaviours and beliefs through a social network. They discovered that Idea Flow sometimes depends more on seeing what people actually do than hearing what they say they do. Seeing other members of our peer group adopting a new idea provides very strong motivation to join in, and it turns out that exposure to others’ behaviour (particularly indirect interactions such as overhearing or observing) is more important for driving this idea flow than all other factors combined. As Pentland says, “When peers adopt a new behaviour, it is hard not to follow along”.

What’s more, the number of direct interactions people had with each other was an excellent predictor of how much their behaviour would change, and the number of interactions also predicted how well people would maintain their new, healthier behaviour. When implementing incentives to encourage these social interactions Pentland found that social network incentives were four times more effective than traditional individual incentive approaches. That is, focusing on changing the connections between people was more effective than trying to get individuals to change their behaviour.

Pentland’s study of behaviour in real time shows us that the most powerful factor in adopting new habits is the observation of how others are behaving, and in particular, the number of opportunities we have to observe this through stronger social networks.

Building Connections to Build Trust

So, what does all this mean for teams wanting to build trust? As stated above, if trust is behaviourally-based, to build trust, teams need to change behaviour. Therefore, once a team has an accurate measure of their level of trust, they need to identify the specific behaviours that are likely to have the greatest impact on building trust and reach agreement on this. For example, do they need to manage expectations better, keep agreements, maintain confidentiality, or admit mistakes? Whatever the behaviours, it is important to restrict this to a maximum of three critical behaviours, as it is difficult for us to make more than one to three changes in behaviour at any one time. However, reaching agreement on these behaviours is just the beginning, not the end of the process.

The team and its leader need to establish mechanisms by which these new behaviours will be adopted. These mechanisms are more likely to succeed if the interventions are based on the following three fundamental principles:

- If changing behaviour is a process, the intervention needs also to be a process over time, rather than a one-off event. This will also support the 80% who are not yet ready to move from Contemplation to Action, and will assist the move from Action to Maintenance.

- Secondly, the more team members are exposed to others behaving differently the more likely they are to change their behaviour. This requires a process where there are either opportunities for team members to observe others demonstrating the new behaviours, or where there are focused conversations and examples of where this is occurring. The more people can observe others behaving differently, and the benefits of this, the more likely they are to follow suit. Ultimately the benefits of the new behaviour have to be visible and outweigh the benefits of persisting with the old behaviour.

- Thirdly, given the importance of social networks in propagating new behaviour, the more the social connections between people can be strengthened the more likely there will be a change in behaviour. A simple measure of this is to ask if the people you talk to also talk to each other. Focusing on changing the connections between people rather than focusing on getting people to individually change their behaviour will create greater social pressure to change their behaviour and will be more likely to succeed.

Finally, creating a team based on trust and mutual respect takes effort and a change in the way each person relates to others. As challenging as this can be, the team itself offers unparalleled power to change our behaviour through harnessing this same desire to belong, and by knowing that we each play a part in the creation of this. Trust is about the choices we make every day, and it begins with each of us. As Professor Pentland says,

“Organisations can be thought of as a group of people sailing in a stream of ideas. Sometimes they are sailing in a swift, clear stream where the ideas are abundant, but other times they are in stagnant pools or terrifying whirlpools. Being part of this (swift, clear stream) allows people to learn new behaviors”

Ultimately the learning of these new trust building behaviours will not only create the trust that results in satisfying and purposeful work but will meet the need that resides at the deepest level within each of us – to feel connected to one another.

REFERENCES

Goldstein, N.J., Cialdini, R.B., and Griskevicius, V. (2008) A Room with a Viewpoint: Using Social Norms to Motivate Environmental Conservation in Hotels. Journal of Consumer Research, Vol. 35, No. 3 (October 2008), pp. 472-482 Published by: Oxford University Press

Pentland, A. (2014) Social Physics: How Good Ideas Spread - The Lessons from a New Science. Scribe USA

Prochaska, J.O., DiClemente, C.C., & Norcross, J.C. (1992). In search of how people change: Applications to the addictive behaviors. American Psychologist, 47, 1102-1114.

Reina, D. and Reina, M. (2015) Trust and Betrayal in the Workplace: Building Effective Relationships in Your Organization (3rd Ed). Berrett-Koehler.