Regardless of whether a team is newly formed, self-organising or part of a more traditional hierarchy, the way authority and leadership is exercised is critical to the team achieving its goals. When this works well, leaders inspire and empower the members of the team, and are able to manage the task and relationship boundaries necessary for the team to perform effectively. When a team is not working so well, the team becomes unproductive, inefficient, or at worst, dysfunctional.

Although many organisations invest heavily in developing leadership skills, they often lose sight of the fact that there are two parts to the leadership equation. Leaders cannot exist without followers and so understanding what motivates people to follow a leader is crucial to a team’s success.

“For leaders to lead, they need not only exceptional talent but also the ability to attract followers.” (Michael Maccoby)

At the core of this relationship between Leader and Follower is our experience of authority. In particular, how authority is exercised and responded to underpins the leader-follower relationship and has a significant impact on the ability of a team to perform their primary task effectively. At its best “good authority” enables the team to perform tasks, use resources, and make decisions that will help the team achieve its objectives. However, as Abrahams has pointed out, “authority is a dynamic phenomenon and thus needs to be regularly negotiated between the leader and the group”.

What’s more, all of us have a different relationship with authority, based on the way our personality formed and our early experiences of authority, from family to school to work.

These early experiences of authority are not only influential in the general development of our personality but, more importantly, our relationship with authority later in life. It influences and shapes how we respond to those in authority, like schoolteachers, managers, and government. These early experiences also affect how we take up our authority as we mature when we are in positions of responsibility, such as being a parent or a leader at work. In other words, these formative experiences of authority shape both sides of the Leader-Follower equation, as it not only affects the way we respond to those in authority, but also how we take up our own authority.

Understanding our habitual patterns of relating to authority can be very helpful in avoiding our “default” settings and being able to respond more authentically and flexibly in any given context. It can also be invaluable in understanding more clearly the differences in the people we are managing. As organisations begin to rely on more complex forms of leadership, such as distributed leadership[1], complexity leadership theory and authentic leadership, understanding what good authority looks like and how it can be exercised becomes even more important.

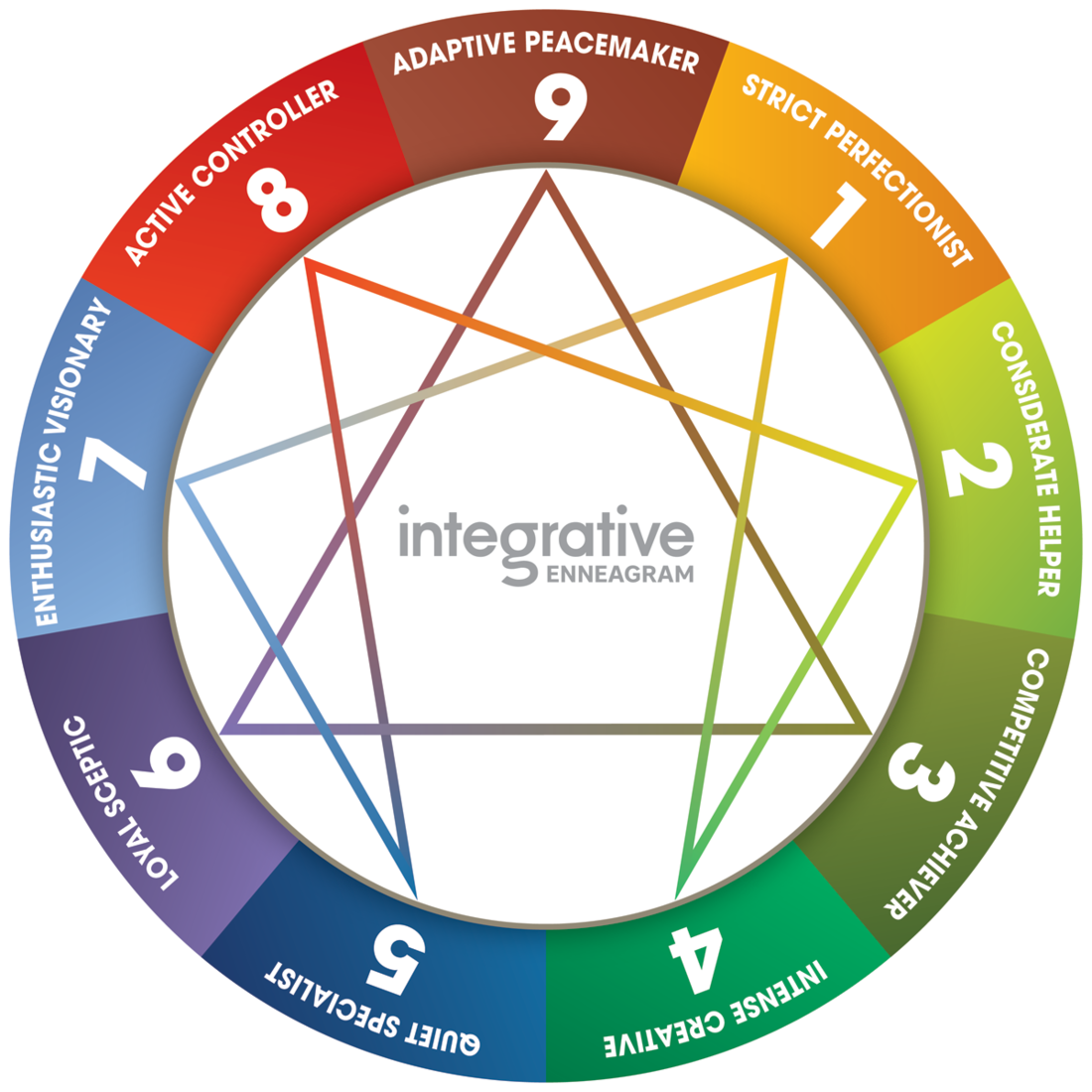

The Enneagram offers a unique way of understanding each person’s relationship to authority based on their Enneagram type. Not only does the Enneagram teach us that all nine types have the potential to be great leaders, but similarly all nine types have the potential to be great followers provided that each leader is aware of the underlying needs of the different Enneagram types.

Below is a brief guide to understanding the first four[2] Enneagram type’s relationship to authority, and in particular what type of authority helps leaders get the best out of each Enneagram type.

Background

Our core Enneagram type represents a distinct way of operating in the world, based on a core drive that guides what we pay attention to and how we seek to get our needs met. In other words, the sort sorts of things we instinctively pay attention to (or don’t pay attention to) and the way we organise ourselves in the world to get what we need. This both consciously and unconsciously drives our thinking, feeling and behaviour. When exploring the relationship with authority we can use the Enneagram to understand more clearly why we act and react the way we do to people in authority, and even the way we typically take up authority.

Ones: The Strict Perfectionist

Driven by the need to be perfect and avoid mistakes, Ones are often most comfortable with more traditional forms of authority. They work well with external rules, routines and clear standards of behaviour. Consequently Ones are often happy to follow a leader and will typically work hard to please their leader by delivering work at the highest possible standard.

However, if they think the leader is doing it the “wrong way” or is too “flexible”, they may interpret this as poor leadership and react in more passive aggressive ways. An example of this is when a leader is inconsistent in the standards she sets, or when they change their position too easily. Ones can respond to this by doing things their own way (the “right” way) and digging in, insisting that the “rules” are followed, or by not adhering to the rules or directives given by the leader. In some cases the One may even rebel against the leader. Ones may also struggle with more fluid or ambiguous work contexts where the rules are unclear, or with distributed leadership where the authority is shared.

Twos: The Considerate Helper

As the “Considerate Helper”, Twos are often driven to contribute to the group and support others, especially those in authority. They are attuned to the needs of the team, and very good at attending to the human aspects of work and managing the relationships within the team. Consequently Twos can appear like the perfect corporate citizen and great supporters of those in authority. Because of this they are often very comfortable supporting the leader and make a great second-in-command.

However, leaders can fall into a false sense of security through the clear and explicit support offered by the Two. As pride fuels their passion, the relationship between leader and follower hinges on the extent to which the Two feels appreciated and valued for their contribution. Being prone to a lack of awareness of their own needs, Twos may support the leader’s agenda without knowing what they want in return, or specifically what they are needing from the leader. When exhausted, overburdened or unappreciated, Twos can end up feeling resentful and get controlling or demanding. Whilst the Self-Preservation Two tends to be less willing to exercise their own authority, Social Twos (the “Ambition” subtype) are very ambitious and the most comfortable with their authority. However, their need to feel important and influential can sometimes result in the Social Two indirectly competing with the leader.

Threes: The Competitive Achiever

Threes are inherently competitive and focused on their own goals, so if these are aligned with the leader or organisation’s goals, they will form a productive and mutually satisfying relationship with authority. Threes often respond well to clear goals, and particularly ambitious or what might be called “stretch” goals, so if the leader can give the Three opportunities to perform effectively, she is likely to be happy and perform well. However, if a leader is too vague in setting these goals, or slow to act, Threes will perceive these to be obstacles to what they are wanting to achieve, become frustrated and even go outside the system to achieve their goals.

Therefore for the Three to relate well to authority there needs to be a clear set of goals and rewards for achieving those goals, along with the autonomy to go about achieving their goals. As such, some Threes may find distributed leadership frustrating and prefer more traditional forms of authority that are clearer. Similarly, in more fluid business contexts, or where the authority being exercised is more relationally oriented, the Three may be dismissive of the authority as not efficient or task focused enough, although this can be an area of growth for most Threes. Even though all three subtypes of the Threes have a drive to appear successful and to achieve goals, the Self Preservation Three is likely to be more covert in their desire for status or recognition, whereas the Social and One-on-One Threes are likely to be more comfortable seeking this attention and praise more explicitly, and respond well to opportunities to shine.

Fours: The Intense Creative

Fours see themselves as unique and special and need room to do their own thing in their own way. Their creativity and uniqueness is central to their identity, and so in this sense autonomy is pivotal to the Four’s satisfaction and willingness to follow. When authority figures provide this degree of latitude, Fours can be great contributors blending their natural emotional intelligence with a passion and energy for the task at hand. Fours are also naturally attuned to connection between people, and particularly the quality of the connection.

For this reason, the degree to which the leader is able to connect authentically with the Four (before moving into task mode) will be critical to the Four’s willingness to follow. If a Four feels dismissed or that the connection is not genuine, he will either insist on creating the connection, or withdraw. Similarly, when Fours experience too much structure or when authority figures are too omnipresent, at least from the Four’s perspective, Fours will feel a loss of their uniqueness and individuality, and a disregard for their inner world, resulting in withdraw and/or finding fault with the authority figure, the system, or both.

Looking at the notion of leadership and followership through the lens of the Enneagram allows us to better understand the specific relationship each Enneagram type has with authority and equips us to get the best out of the leader/follower relationship, regardless of which role we occupy. In my next article I will continue this guide to understanding each Enneagram type’s relationship with authority, focusing on Types Five to Nine.

[1] Distributed leadership is a group activity that works through and within relationships, rather than individual action. "Distributed leadership is not something ‘done’ by an individual ‘to’ others, or a set of individual actions through which people contribute to a group or organization... [it] is a group activity that works through and within relationships, rather than individual action." (Bennett et al. 2003, p. 3)

[2] I will cover Types Five to Nine in my next article.

I am grateful to Ginger Lapid-Bogda and Beatrice Chestnut for their pioneering work in this area

| Abrahams, F. (2005) | A systems psychodynamic perspective on dealing with change amongst different leadership styles. (Unpublished masters dissertation, UNISA). |

| Bennett, N., Wise, C., Woods, P.A. and Harvey, J.A. (2003) | Distributed Leadership. Nottingham: National College of School Leadership. |

| Chestnut, B. (2017) | The Nine Types of Leadership. New York: Post Hill Press. |

| Lapid-Bogda, G. (2007) | The Enneagram in Business. https://theenneagraminbusiness.com/ |

| Maccoby, M. (2004) | Why People Follow the Leader: The Power of Transference. Harvard Business Review. |